PET is a cannabinoid that is produced by liverworts, and it acts exactly like THC, interacting with our endocannabinoid system to kill pain.

Can you get cannabis benefits without the cannabis? A new study from the journal Science Advances suggests that a chemical compound produced by liverworts is so structurally similar to THC that it may be a new source of pain relief.

PET and THC Similarities

The substance in question is called perrottetinene (or PET), and it was first discovered in 1994. At the outset, it was already thought to be a cannabinoid, but recent research is the first to confirm these suspicions. That means that, to date PET is one of the only naturally occurring, medicinally active cannabinoids not produced by the cannabis plant. There are other cannabinoids in the plant world, such as CBD, found in hops.

PET interacts with the human body’s endocannabinoid system in much the same ways as THC, attaching to CB receptors in the brain and reducing feelings of pain. You can think of it like the Diet Coke version of THC. It’s not as potent as THC, but the effects are noticeable.

Liverworts Kill Pain?

The name “liverwort” refers to a division of non-vascular plants that resemble mosses. Some have structures that look like leaves, but do not perform the same functions or have the same internal makeup of true leaves (hence the non-vascularity). Liverworts are often considered lower plants because they were among the first to evolve and are relatively simple.

Out of the more than 9,000 species of liverwort, only three produce PET. All three are in the Radula genus, and grow in three very specific habitats: Japan, Costa Rica, and New Zealand.

Difficulties of Studying Liverworts

All three species produce the cannabinoid. However, it’s produced in such minute qualities that it’s been difficult for scientists to obtain enough PET to do a suitable study.

And that’s where synthetics come in. Analyzing just a bit of naturally occurring PET, scientists were able to engineer a lab-made substance that mimics the structure and behavior of the molecule.

Just like THC, PET occurs within the liverwort plant as an acid. Just like THC, PET acid is psychoactive. Its properties activate through heat mechanisms like drying or smoking.

Liverworts: A Recognized Cure for a Long Time

That’s why apothecaries sell dried samples of PET-producing liverworts as a natural remedy and incense. It hjas been in use for decades, if not hundreds of years. In recent years, sales of the plant as a recreational drug promising a cannabis-like high have exploded across the globe.

But the slight amount of PET per plant means that quality control is difficult. Individual anecdotes of internet liverwort sales range from the exclamatory to unimpressed. When dealing with a chemical that’s rare, it’s hard to guarantee that buyers will get their money’s worth, even if sellers are acting in good faith. Before synthetics, the rarity of PET severely limited the viability of using PET as an active ingredient in new drugs.

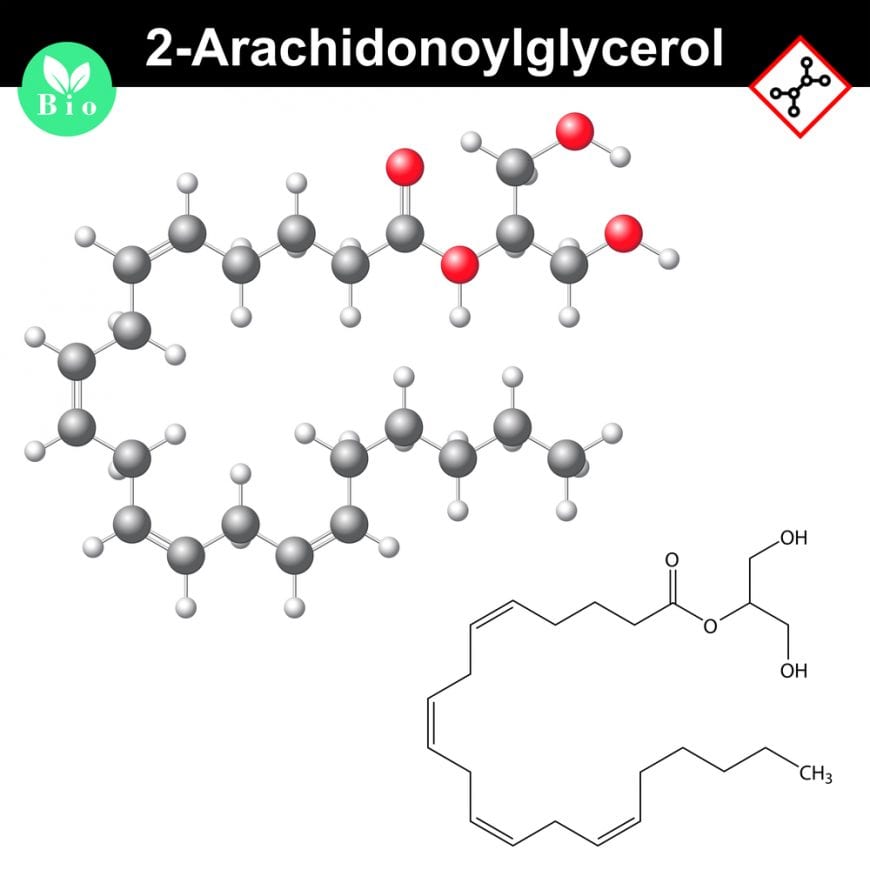

The pharmacology of PET is interesting. While THC reacts with the CB1 receptors in the endocannabinoid system exclusively and cannabidiol (CBD) reacts with CB2 receptors, PET seems to do both, albeit on a different scale.

The CB receptors that link PET to the endocannabinoid system play a large role in regulating certain hormones and inflammation responses. PET significantly lowered the levels of prostaglandin in the brain. This worked in much the same way that the human body-produced cannabinoid 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) does. This endocannabinoid appears throughout the body’s central nervous system, but most notably in the brain. It plays a vital role in keeping gray matter running smoothly.

In Conclusion, the Importance of PET

The discovery of PET and its synthetic means big things. It means them not only for drug discovery and pharmaceutical uses, but also for our understanding of biology and evolution.

The PET producing plants uniquely suit their geographic locations. Because of this, they did not likely evolve together then split apart. A much more likely scenario is that these plants developed psychoactive elements separately but convergently. For some reason, these moss-like plants found it evolutionarily advantageous to produce a very small amount of this THC-like substance.

Of the 20,000 species of bryophytes, only three evolved this way. Scientists, however, don’t know why. However, the independent evolution of similar features signals a real benefit in producing PET.

While biologists struggle to understand the history of PET, medical scientists may begin to harness its psychoactive properties. The researchers believe that new drugs derived from PET will find a spot in local pharmacies. This is thanks to PET’s effects, which they liken to a very subtle strain of THC.

Here’s hoping they’re right.