Political correctness is zipping shut our common sense. And the great irony is that ‘marijuana’ may be the most politically correct term of all.

People take great offense when you speak the wrong term to them: Marijuana. Weed. User. Consumer. Drug. You try to pull the last one, and I guarantee that “cannabis is NOT a drug” is going to come flying in your face. We live in a time where language is a measure of the elevation of our social consciousness. Conflict-seeking cynics decry “political correctness” as an affront to their free speech while so-called social justice warriors police everyone’s language, only to change key portions of what is “acceptable” by the next week. Recently, a new argument has come out of it all – whether or not the word marijuana is racist.

Is the Word Marijuana Racist?

I’ve been in trouble over this one before, and this won’t be the last of it; I sometimes say and write “marijuana.” Why? Well, for one, “marijuana” is typed into search engines, like Google, far more often than “cannabis.” And with that, I am exploiting algorithms when I write “marijuana.”

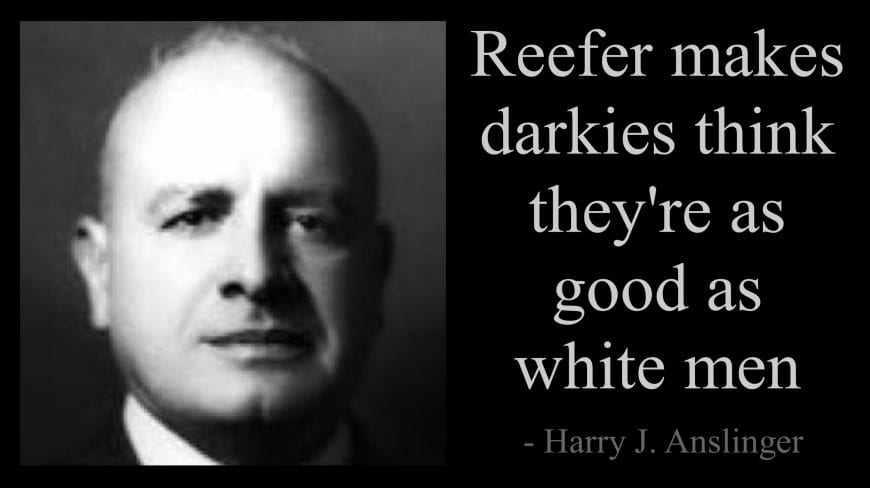

Then there’s the fact that the word “marijuana” originated from Mexico. Mexican immigrants in the early 1900s already used this word to describe Cannabis sativa. When Harry Anslinger and the American prohibitionists stoked the flames of Reefer Madness, they ensured their fellow Americans would perceive the term and the plant as a dirty Mexican import into a pure, Christian nation.

The cultural hijacking of “marijuana” – a hijacking by prohibitionists, that is – continues to this day. In 2018, we still see anti-cannabis legislation that refers to the plant as “marijuana,” or worse, “marihuana,” harkening back to those Reefer Madness days. Which is real funny when you consider Cannabis sativa was initially brought to the New World by white Dutchmen, not Mexicans.

Whether The Word Marijuana is Racist Depends on Who You Ask

In legal jargon, “marijuana” refers to cannabis (or cannabis products) that contain a significant amount of THC (more than 0.03%). Cannabis that contains less than 0.03% THC is legally designated “hemp.”

Activists and advocates in our movement are somewhat split on whether we should ditch the term “marijuana” altogether. Personally, I think it’s racist to treat “marijuana” like a bad word, because, in my opinion, it reinforces the racist stigma that legislators attach to the word. I find “marijuana” to be an incredibly beautiful word. It slides off the tongue like honey.

Is The Word Cannabis Racist?

However, I am not Mexicano by any stretch (as far as I know), so I don’t really get much say on the matter. Which is why I try to use the term sparingly, and I try to restrict myself to only using it when referring to the word itself or a proper title that includes it.

What about “cannabis,” then? “Cannabis” is a good, neutral term. It’s the “scientific” term, so it’s not only semi-official, it’s the correct term to use, right?

Here’s where I ruffle some feathers. I apologize in advance.

I would argue our community’s borderline obsession with the word “cannabis” is, itself, a little racist. Hear me out.

Historians agree that the word “cannabis” comes from the Greek “kannabis,” which means, uh, cannabis. Herodotus used “kannabis” to describe a plant that the Scythians traded throughout the Greek empire. And if we believe everything Herodotus tells us (trust me, he had some wild stories), then the Scythians may have been one of the world’s first hot-boxers, as this seemed to be their preferred method for getting lit.

Linnaean Categorization

Fast forward nearly two thousand years, and we get a guy named Carolus Linnaeus. Linnaeus is a bit of a legendary figure in my discipline – biology – because he undertook the Sisyphean task of classifying every single life form known to humanity at that time. Ha! And you thought Noah had it rough? Linnaeus included plants and microorganisms in his global biology roundup, something Noah apparently didn’t do.

Linnaeus, like any good European scholar, knew Latin and Greek. He was Swedish, but he understood he required a language more universal than Swedish to describe Earth’s creatures. So, he combined Latin and Greek to create families, orders, phyla, etc. to get everything neatly categorized so future biologists knew what the hell other biologists were talking about.

Cananbis is Western

And therein lies the kicker. “Cannabis” is a distinctly Western word (as far as we know), and it’s classical Greek, at that. Cannabis advocates today will eschew “marijuana” as slang, as another racist pivot exploited by prohibitionists. Yet the activists wholeheartedly embrace a Greek term for the plant because that’s what an esteemed European scientist decided on almost four centuries ago.

Why don’t we use the Chinese ma to discuss cannabis? Why not the Indian ganja, which comes from the Ganges River? I’ve been in a number of arguments with people who think “ganja” is slang; it most certainly is not. Or, how about bhang, an ancient Indian term that refers to both a cannabis mixed drink as well as the “narcotic form” of the plant?

Do we avoid using these other “first terms” because we’re not being racially prejudiced? Or is it because we are?

Where Did “Kannabis” Come From?

Archaeologist and linguist, Elizabeth Barber, tried to decipher the linguistic origins for “kannabis” in her book Prehistoric Textiles. She notes the Greek “kannabis” is the first instance of the plant’s undeniable reference, However, she also notes that this word didn’t originate with the Greeks. “Kannabis” is likely a perversion of some Indo-Iranian word brought to the Greeks by the Scythians. The Indo-Iranians likely used something along the lines of “kannab,” which she believes is just the backwards form of “bhang.”

(Side note: Barber has a fascinating hypothesis that the Indo-Iranian spelling for the intoxicating form of cannabis – the “marijuana” form – was simply their variant of the word “hemp” spelled backwards. Because that’s how prehistoric shamans and ancient priests would commune with the spirit world, by doing things backwards. When consuming psychedelics, a shaman would say the names of these plants and fungi in a backwards fashion. If you’re curious about this, check out her book. It’s got a boring title, but I assure you, if you’re into linguistics, the content is not boring.)

So, we don’t know where the word originally came from. I have a suspicion it came from the Bactrians, yet I can’t find any sources on their terminologies for the plant. Therefore, we might as well settle on “cannabis” for now, even if “cannabis” is likely just a modification of the first word for the plant.

What About Weed?

“Weed” probably got popular during the American Counterculture era.

I take heat for using “weed” in my writing too. Why do I like it so much? Because “weed” has no scientific designation. It’s not a scientific word. You’ll never find biologists classifying any plant as a “weed,” because the word indicates a plant that nobody wants. “Annoying” isn’t a Linnaean category. For example, dandelions are nutritious, edible plants with medicinal properties, but the average American home owner doesn’t want dandelions on their lawn. Hence, we consider dandelions weeds.

Weedy plants usually bear some specific characteristics. They may or may not be native to their area. But they tend to proliferate rather easily and quickly, which is why Americans invest millions of dollars each year on spraying weed killers across their precious lawns.

Let’s review: difficult to get rid of, with a tendency to pop up anywhere and everywhere; a plant that’s a nuisance to uptight individuals who obsess over imposing strict, wholly artificial order over their inherently chaotic worlds. That’s what defines a weed.

And that, my friends, is cannabis/marijuana.

Ed Stewart

Do we need medical cannabis, yes to control the product. But it must be made cheaper than the stuff on the street. If legalized you can have MJ mixed with other drugs unfortunately, there is always that wicked group of people looking to get you “hooked” so they can have your $$$. So the patients are being abused in having pay higher prices than what you can get off the street, thus encouraging street sales.